I hate friends. No idea why I used a Friends type title. Anyway. This is about me not making a wind tunnel model.

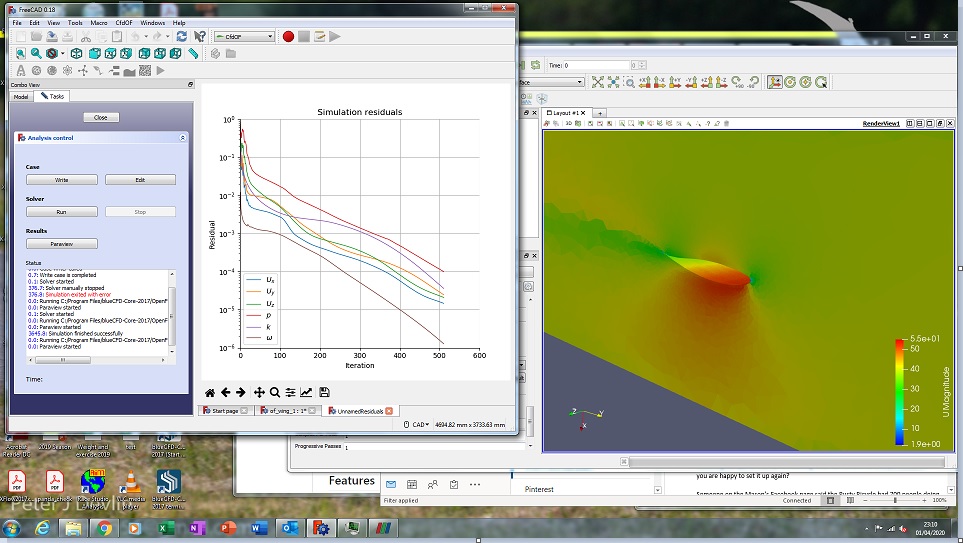

Unless you are supremely gifted, and as we all know I’m not, your first goes at anything are likely to be a bit, well, er, rubbish. In fact I personally don’t think a typical person can learn to do something unless they actually enjoy being crap at it. So you have to get in there, have a go, mess up and then see where it all ends up. (36 years after making my first toy aeroplane I won an event at the Nationals, so it isn’t always a rapid process.) Where I’m headed with racing cars means that I need to get a grip on aero (see previous stuff on CFD) and that means wind tunnel testing in some form. Which means I needed to get in there and mess up a wind tunnel model.

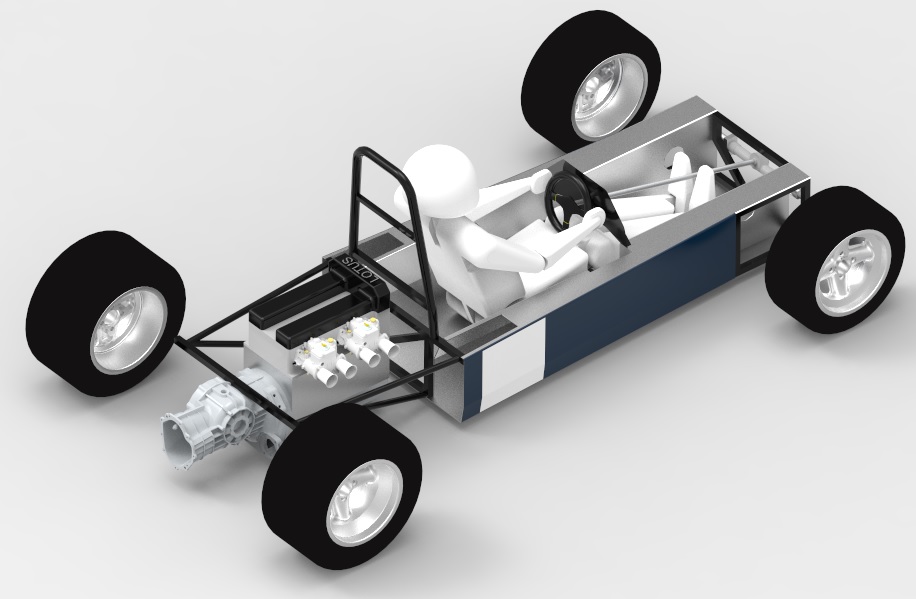

I used to exchange tweets with the recently departed and already much missed Richard Divila. And in one exchange he said that I’d be surprised how much you could learn from a really basic wind tunnel. And I guess that means from a pretty basic model. My son, is, as I write this, finishing his dissertation, which might not surprise people to learn is a CFD study of a racing car. In fact the one I used to form the basis of Openfoam work in the last blog. And for that the initial intention was to do some wind tunnel validation of his Fluent work. It’s entirely possible that even without Covid19 we might not have got round to it. But I did get what is very much a comic book first hack out of my system. And that’s a good thing; it really is, because it gets you somewhere good. So what have I learned

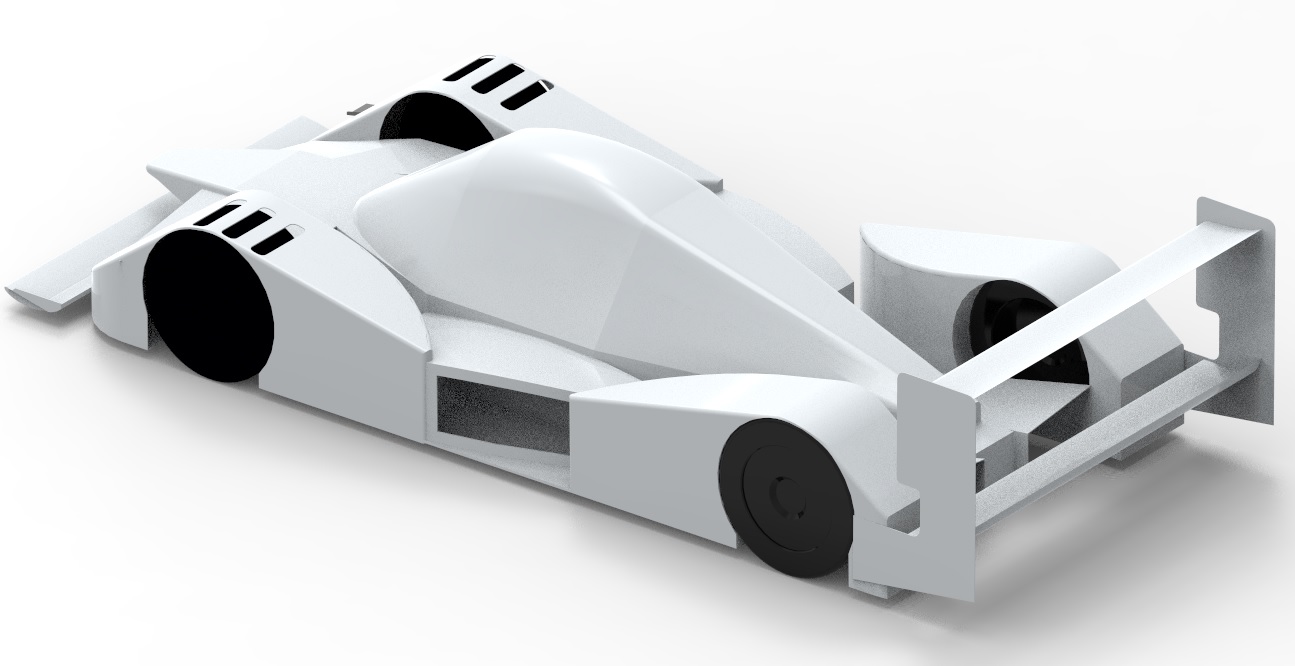

You can’t 3D print everything: Unlike the current UK government I don’t think 3D printing is the only manufacturing show in town. It plainly isn’t, but this project was my excuse to get a printer. I chose to get a Dremel because I love their stuff. It was a great choice and their aftersales service is really good, mind you it had to be after the first one didn’t really work. And I’ve learned a lot, especially about DFM, (Design for Manufacture) in this specific instance. I’ve been suprised in a good way about some of the stuff I’ve managed to make and surprised in a bad way. I still haven’t changed my mind about the fact that 3D printing, at least with the machines I’ve used, is like machining something on a worn out milling machine – you can do it but it takes a lot of effort. But I am pretty sure I could make half decent body panels for models up to about 20%. What really aren’t good enough are the wheels. They didn’t ever come out well enough, especially when I can machine a set from solid quite easily.

One area where the printer really comes into its own is the production of small brackets. These can be produced quickly in reasonable batches. You’ve got to love that.

Anything that involves thin flat sections should be made from thin flat material, because if you print these you need to make them significantly thicker than scale and the surface finish won’t be good enough. A small CNC milling machine would be really useful here. Floor components, wing end plates and other bits could be profiled from thin carbon fibre sheet. The results would be pretty good.

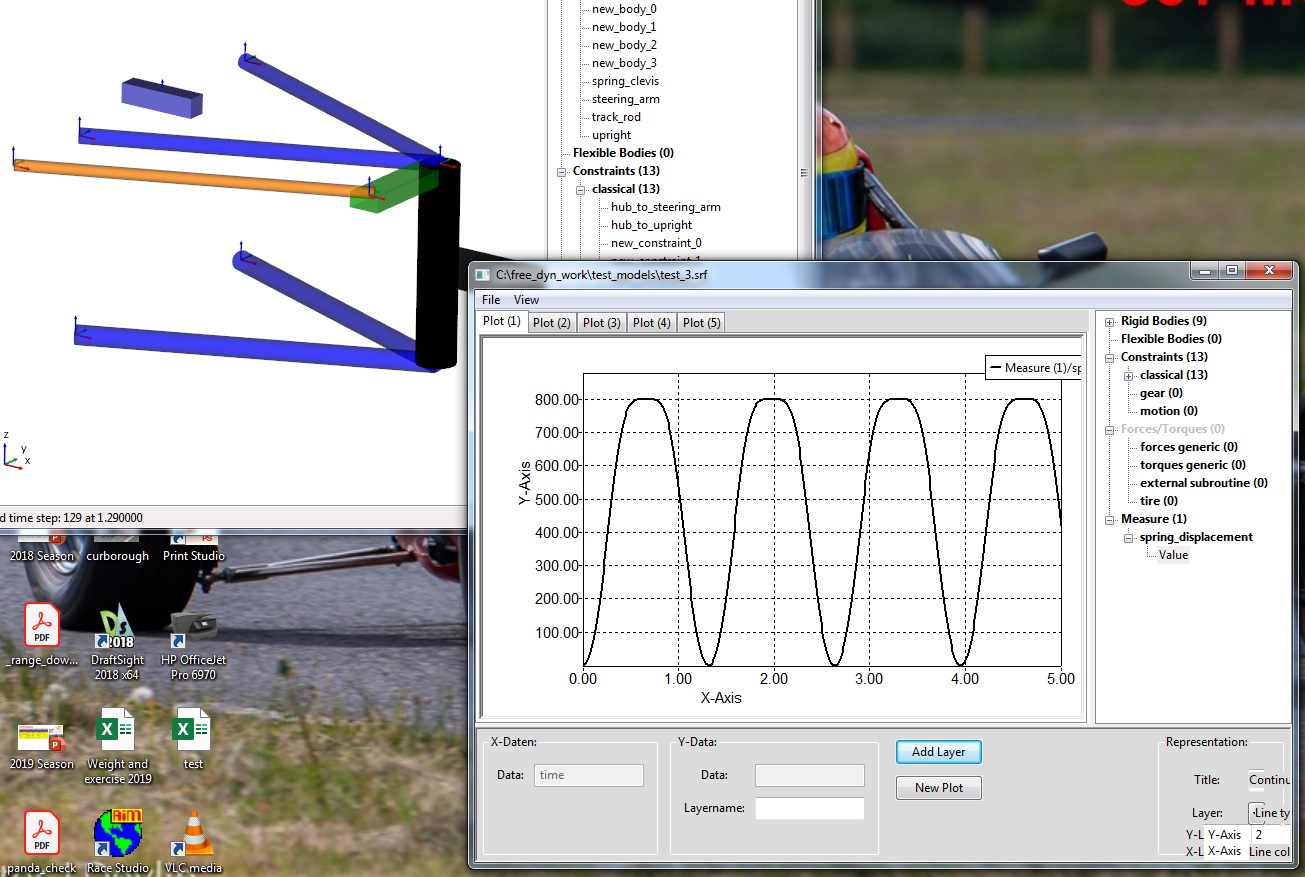

Plainly to be useful the model needs to be very adjustable, and in its current form it isn’t. Ride height and rake need to be controlled very accurately. I’d say that what I need is some form of cross slide arrangement to support the model from a sting. Ebay appears to be awash with them. So that’s that sorted. Another thing that needs to be easily adjusted is wing position and angle of attack. I’ve thought long and hard about this and the only really neat solution is to use a series of mounting plates of different dimensions. That small CNC mill again. And finally the hack model uses a completely 3D printed tub. What it really needs, and I’ve heard this from several sources is a central spine, which is what joins the model to the sting and the wings to the model.

And finally the wings. Obviously these have to be pretty accurate, and the ones I made kind of were. They were printed in vertical sections and then assembled on a carbon rod. As a first stab OK and they would have been reasonably representative. At a larger scale I think this approach would have been fine. So lets describe wing manufacture as a work in progress. But at least we are in the game now.

It’s quite unlikely that this not really good enough model will ever see the inside of a wind tunnel. (With a bit more work it would be a useful exercise though) But it has taught me a lot about making things with AM and what a useful model might actually be like. So not building a wind tunnel model has been a hugely useful exercise if I ever do it for real. Meanwhile the CFD activity continues..